The mystery of Rails’ lib/ folder

📚

2023-12-23

Update 2024-02-19: With the release of

packwerk 3.2.0, the instructions in this article now

work as originally intended again. The article has been simplified

to reflect this.

In Ruby on Rails applications, one of the directories that

come with the default structure is lib/. What is it

for? How should it be used? And why should you care?

Used well, lib/ is a very powerful tool that can

declutter an application, reduce cognitive load and improve

developer productivity. But it’s often not used well.

The official Rails guides say it’s supposed to contain “extended modules for your application”. I don’t think that’s a useful definition. I’m not even sure what it means.

Another idea that I’ve heard often is that the actual

application should live in lib/. The earliest source

I could find is a

2011 blog post by Corey Haines:

Rails is not your application. It might be your views and data source, but it’s not your application. Put your app in a Gem or under

lib/.

I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but if you’re using Rails as intended, it is indeed an integral part of your application. That’s what distinguishes frameworks from libraries.

If you’re using libraries, you’re following the Hollywood Principle: Don’t call us, we’ll call you. You have control over the application. If you’re using a framework, the framework calls you. In other words, you’re just filling in the blanks in a pre-defined structure.

And it’s especially pronounced in Rails thanks to the Active Record pattern. Active Record is all about mixing data access logic (Rails!) with domain objects (your application!).

So, what

is lib for?

You can divide the code in your application into two categories: code that is specific to your application’s core domain, and code that is more generic.

DHH, the creator of Rails, stated:

lib/ is intended to be for non-app specific library code that just happens to live in the app for now (usually pending extraction into open source or whatever). Everything app specific that’s part of the domain model should live in app/models (that directory is for POJOs as much as ARs).

Code that’s not specific to your application’s core domain may concern responsibilities like HTTP clients, authentication and authorization, (generic) serialization and deserialization, and so on. For these concerns, we usually don’t write the code ourselves - we use libraries, gems. Almost always those are third party gems from rubygems.org.

But what if what we need is not available in a well maintained library? What if the functionality we need is so small that it doesn’t warrant introducing an external dependency? Maybe it’s something that we can easily write ourselves?

You may want the code to live in the same repository as your

application, even though it’s not specific to your application’s

domain. Luckily, Rails is prepared for this scenario. That’s why

app/ and lib/ folders exist!

Library code within your repository is still library code. So

it should go into lib/.

It’s right there in the name!

💡 lib/ is for libraries.

Boundaries

The main advantage of separating library code from your application instead of just lumping it in with all of your other stuff is the reduction of cognitive load. Ideally, you can look at the library code and understand it without having to know any of the details of your application. The less you as a developer need to know to do your work the faster you can get things done, delivering value to your users and checking items off your to-do list.

Robert Martin writes in Clean Architecture:

Software Architecture is the art of drawing lines that I call boundaries. Those boundaries separate software elements from one another, and restrict those on one side from knowing about those on the other.

Let’s do some Software Architecture! 🧑💼

If software element A doesn’t know about element B, that also means you can understand element A without having to understand element B. In practice, “A doesn’t know about B” means that A doesn’t have source code dependencies (AKA static dependencies) on B.

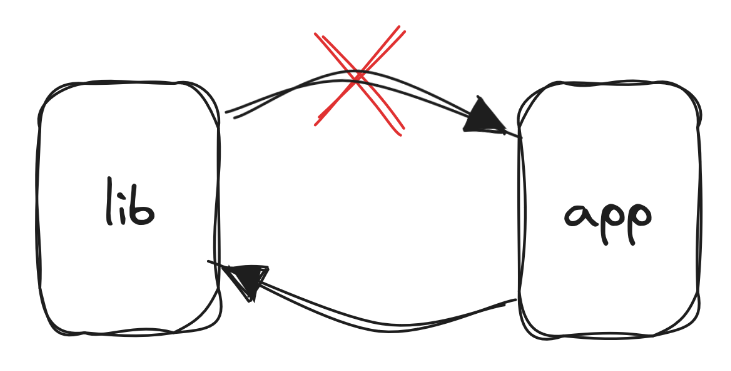

Remember, we want to be able to understand our libraries

without having to understand or know any details of the

application. Therefore, the code in lib/ should not

have dependencies on the code in app/.

💡 The application depends on its libraries, but libraries never depend on the application.

Complication: Autoloading

In Rails versions before 7.1, lib/ is not

autoloaded, which means that if you want to use code from

lib/ in your application, you need to explicitly

require it. While in theory this is a good thing because it makes

a dependency explicit, requiring a file explicitly will still add

its contents to the global namespace. That means requiring a

file once, in one place, will make it available everywhere,

and implicit dependencies on it will creep in. So the advantage of

explicit dependencies doesn’t really exist in Rails apps in

practice. Also, without autoloading, the code in lib/

will not be reloaded after making changes locally, which is

inconvenient.

But you don’t want to autoload all of lib/ either.

There’s likely a lot of code in there that your application

doesn’t need to run in a production environment, like rake tasks.

Autoloading it in development implies eagerloading in production,

which would slow down application startup, use up additional

memory, and potentially cause bugs in production.

One good workaround has been proposed by prominent Rails contributor and autoloading expert Xavier Noria:

The best practice […] is to move that code to

app/lib. Only the Ruby code you want to reload, tasks or other auxiliary files are OK inlib.

Any folder under app/ will be autoloaded by

default, including app/lib/.

In Rails 7.1, a new default was

introduced to autoload lib/, specifically

omitting the subfolders lib/assets/,

lib/tasks/ and lib/generators/, which

means you don’t need Xavier’s workaround anymore.

So, going forward I will assume that the library code your

application relies on is autoloaded - either it is in

app/lib/ or it is in lib/ and autoloaded

via Rails 7.1’s config.autoload_lib.

💡 Your application libraries should be autoloaded.

Making it so

Because local libraries and application code are versioned and

tested together, it is easy to accidentally break the boundary by

introducing a dependency on the application to the code in

lib/. Most of the time, this will be a call to a

model class. In a small, well aligned team, you can probably avoid

this erosion for a while. But as the team grows and the

application ages, at some point boundary violations will creep

in.

The problem with an incomplete boundary is that you can’t trust it. You can’t be sure that the code you’re looking at is independent of the application; you have to check every time, and your cognitive load increases. Incomplete boundaries will also erode more quickly.

But I have good news for you: Because your library code is

autoloaded, you can use a nifty little tool called

packwerk1 to enforce the

boundary.

Enforcing your library boundary with packwerk is

easy. Start with

bundle add packwerk --group "development, test"

bundle binstub packwerk

bin/packwerk initAs part of the initialization process, packwerk

will place a package.yml file in the root folder of

your application, which defines the root package. All your code

that is not explicitly in another package is in the root

package.

⚠️ In the following, replace lib/ with

app/lib/ if you’re using the app/lib/

setup.

To enforce a boundary between application code and library

code, we just drop another package.yml file into the

lib/ folder:

# lib/package.yml

enforce_dependencies: true

dependencies: []This tells packwerk that lib/ is a package, code

inside of it should respect the declared dependencies, and we

don’t want it to depend on any other package (not even the root

package).

💡 Run bin/packwerk validate to validate

packwerk’s configuration files, which encompass

packwerk.yml and all of the package.ymls

you may have.

Now, if we run bin/packwerk check, we get a list

of all the violations of the boundary we just defined. Ideally,

this list is empty. Maybe there are a few entries there that you

can easily rectify. But more likely, you have a long list of

violations that you’ll want to fix one by one.

To facilitate this, packwerk has a ratcheting mode where it

accepts existing violations but complains about new ones. You can

record existing violations by executing

bin/packwerk update-todo. This will create to-do

files for each package with violations. Check them into your

version control system.

To get the most out of packwerk you will want to

add a step to your CI system that executes

bin/packwerk validate (to validate the configuration)

and bin/packwerk check (to enforce the

boundaries).

Conclusion

Rails’ lib/ folder is more than just a directory.

It’s a manifestation of a fundamental software engineering

principle. By understanding and applying the concept of

architectural boundaries, developers can create more maintainable,

scalable, and understandable applications.

For many Rails developers, this is a new skill to master, which

can seem daunting. However, the lib/ folder is a

great place to start, and packwerk can guide you on

your way.

Further Reading

packwerkhas extensive usage docs.- Awesome former teammate Maple Ong wrote a great blog post about Enforcing Modularity in Rails Apps with Packwerk.

- You may also be interested in my article on the Shopify blog about the larger context of my modularity work at Shopify.

- For much shorter feedback cycles, if you’re using VS Code, you can install packwerk-vscode to see violations as you type.

- To avoid or resolve dependency cycles, you’ll quickly find yourself needing a working unserstanding of inversion of control and dependency injection. Create abstractions and invert dependencies so they are opposed to the control flow. This probably deserves its own article.

I developed the idea and core functionality of

packwerkin 2020 during my time at Shopify, supported and inspired by a lot of very smart people around me. Together with the team we later polished the tool and open sourced it, and it has since found significant adoption in the Ruby on Rails community.↩︎